Barrier 4: Some constituents are resistant to agency engaging and serving broader constituencies

Fear of loss is well-established as a common factor in resistance to change. Some constituents may be resistant to agency efforts to engage and serve broader constituencies based on fear of loss of influence on agency decisions or concern about the effect of redirecting agency resources to new programs. Manfredo et al. (2018) reported evidence of a cultural backlash that may be occurring in response to a shift in wildlife value orientations. If enough resistance is expressed, it could impede agency efforts to engage and serve broader constituencies.

Strategy 1: Reduce resistance by demonstrating the conservation benefits of broader engagement and the agency’s responsibility for serving all members of the public.

Although it may not be possible to eliminate all resistance to broader engagement, an agency may be able to reduce it by reassuring traditional constituents that expanding engagement is not a zero-sum game and that their interests will continue to be supported. Demonstrating the conservation benefits of engaging and serving broader constituencies, and effectively communicating the agency’s obligations to all members of the public under the public trust doctrine can help. It is likely that among those who initially oppose an agency’s efforts to serve broader constituencies, some may become supporters once they understand they share conservation goals with other groups. Support may also increase when the benefits of having more diverse support for the agency are communicated. Some members of the public may be unaware of the responsibility agencies have under the public trust doctrine to treat all members of the public equitably. By understanding, addressing, and alleviating the fears and misconceptions of initially resistant individuals, an agency might recruit more advocates for broader engagement and reduce the influence of others whose resistance is unlikely to waver.

Step 1: Identify the issues, perceptions, and beliefs that generate resistance to engaging and serving broader constituencies.

Tactic 1: Use social science research to understand the values, perceptions, and beliefs of people who resist broader engagement.

Rather than operating on assumptions, it is imperative to identify the specific nature of and basis for people’s resistance in order to select appropriate actions that will effectively increase support. Several studies have identified, at various scales, the values, perceptions, beliefs, and motivations people hold toward wildlife and nature. Other studies have investigated the basis for resistance to engaging more diverse interests in agency programs. This literature, supplemented by local research, may help an agency understand why some constituencies resist expanding engagement.

Tactic 2: Meet with individuals or organizations that are resistant to explore the reasons for their position.

In addition to conducting research, agencies should interact directly with constituencies who resist expanded engagement. First, direct interactions will enable the agency to gain additional understanding of the basis for resistance. Second, making the effort to meet with constituencies who resist expanded engagement demonstrates that the agency recognizes them as having legitimate interests and gives the agency the opportunity to establish a dialog that is essential to understanding the reasons for resistance. It may be necessary or appropriate at first to use trained facilitators from outside the agency to conduct structured focus groups or other interactive techniques to identify the core concerns, fears of loss, and perceptions that produce resistance to an agency’s efforts to engage broader constituencies. Eventually, direct interactions should establish a level of trust, through which the agency can address the identified causes of resistance.

Constituent culture success story: recruit hunters and anglers

The Ohio Department of Natural Resources has created a “Mentor’s Challenge.” Employees are encouraged to introduce residents to hunting, fishing and other forms of outdoor recreation. Employees are rewarded for these activities and this challenge has the added dividend of exposing staff to diverse audiences.

Step 2: Demonstrate continued commitment to current constituencies.

Tactic 1: Establish or strengthen working relationships with hunter, angler, and trapper organizations.

Most agencies have strong working relationships with hunter, angler, and trapper organizations, but paying additional attention to these organizations at the same time an agency seeks to engage broader constituencies may reduce the concern that the agency is turning away from traditional constituencies. Adjusting workloads to provide time for staff to participate in meetings with organizational leaders or their members, or targeting communications to these groups are ways an agency can demonstrate a continued commitment to hunters, anglers, and trappers.

Tactic 2: Engage respected, credible spokespeople among the hunter, angler, and trapper communities to help reassure opponents of broader engagement of the agency’s continued commitment to its traditional constituencies.

Many credible outdoor writers and others who are respected by, or are influencers of, hunters, anglers, and trappers understand the benefits of engaging broader constituencies. Encouraging these individuals to help carry the message to their audiences may be more effective than communications from the agency.

Step 3: Demonstrate the shared values and conservation benefits of collaboration with broader constituencies.

Tactic 1: Share results of the Nature of Americans study with broader constituencies.

The Nature of Americans Report documents the strong interest most Americans have in nature and the value the public places on conservation. An agency can use this information to develop state/province-specific and issue-specific messages that focus on areas of agreement. These messages can be used to offset rhetoric that emphasizes differences.

Tactic 2: Identify local conservation initiatives with broad appeal that benefit from a broader base of political and financial support.

Most agencies should be able to identify a conservation challenge that cannot be addressed without the support of diverse constituencies. Examples may include large-scale habitat conservation or restoration projects, potential effects of a development on critical fish and wildlife resources, or the threat of invasive species. By engaging both traditional and broader constituencies in efforts to address the challenge, an agency can demonstrate the value and need for expanded partnerships. Generating support for Recovering America’s Wildlife Act may also be an example of an effort around which diverse constituencies can come together to support increased funding for agencies.

Tactic 3: Summarize and promote the results of diverse stakeholder focus groups, collaborations, partnerships, and problem-solving exercises.

Fear of loss not only contributes to resistance to engaging and serving broader constituencies, it also affects agency staff who may be hesitant to try new efforts that bring more voices to the conservation table. By documenting past conservation achievement stemming from broader constituent engagement, agency staff and leadership may be better prepared for outreach efforts that increase the agency’s relevancy because they can cite past success and alleviate concerns of losing current support.

Step 4: Build relationships between constituencies based on shared values, beliefs, and conservation priorities.

Tactic 1: Engage current and potential new constituencies in ways that build relationships among them.

Relationships and trust are built on personal interactions. It is easy to apply an us-versus-them paradigm to people with whom an individual has no relationship or who hold differing values and beliefs. Modern electronic communication methods and social media, which allows people to attack others with anonymity, amplifies this problem. When people with deeply divergent values are placed in a setting where they can interact on a personal level, a very different dynamic occurs. With time and facilitation, participants can come to recognize the human value of those with whom they disagree and begin to respect the others’ conservation or nature values. Giving a diverse group a challenging problem to address can provide the basis for building understanding and trust. The Governors Roundtable on the Yellowstone Grizzly Bear Conservation Strategy and Montana’s Wolf Management Advisory Council are two examples of processes that brought together diverse interests on a conservation issue. Encouraging broad constituencies to interact can also serve to build relationships. For example, a hunter or angler taking a nonhunter/angler out hunting or fishing can be a way to demonstrate how such activities support conservation. Similarly, having hunters/anglers accompany nonhunters/anglers on birding or nature hikes can provide an opportunity for these individuals to share both an experience and their mutual passion for wildlife.

Tactic 2: Engage current and potential new constituencies in habitat restoration projects.

One of the most commonly shared values among broader constituencies is the importance of healthy fish and wildlife habitat. By engaging diverse interests in efforts to restore habitat, an agency can demonstrate to all parties their shared conservation values. Habitat restoration projects may have broader appeal than habitat conservation projects because the latter may involve precluding development, foregoing resource extraction, or transfer of land title to a government or nongovernment entity, to which some people object. Habitat restoration focuses on fixing a problem to benefit fish and wildlife that most people can support.

Tactic 3: Provide opportunities for current and potential new constituencies to share their stories with each other.

People often communicate best through storytelling. Allowing diverse constituencies to tell their stories to each other in a facilitated, noncompetitive, and respectful way can demonstrate people’s shared commitment to, and passion for, conservation and allow various constituencies to take and share credit for conservation successes.

Step 5: Increase awareness of the agency’s obligation to serve all members of the public.

Tactic 1: Consistently communicate the full scope of the agency’s obligations under the public trust doctrine.

Under the public trust doctrine, government holds fish and wildlife in trust for everyone, including both current and future generations. To fulfill this trust responsibility, an agency must consider the values, interests, and desires of all members of the public equitably. Engaging broader constituencies is not only a good thing to do for conservation, it is also a legal, fiduciary obligation (Smith, 2011). By consistently communicating this broad responsibility, an agency can build awareness and understanding of its obligation to all members of the public. Because most Americans highly value fairness, this increased awareness may reduce resistance to agencies engaging broader constituencies.

Other Resources for Barrier 4

The North American Waterfowl Management Plan is a model for building relationships and collaboration among hunters and bird watchers. (Milling et al. 2019)

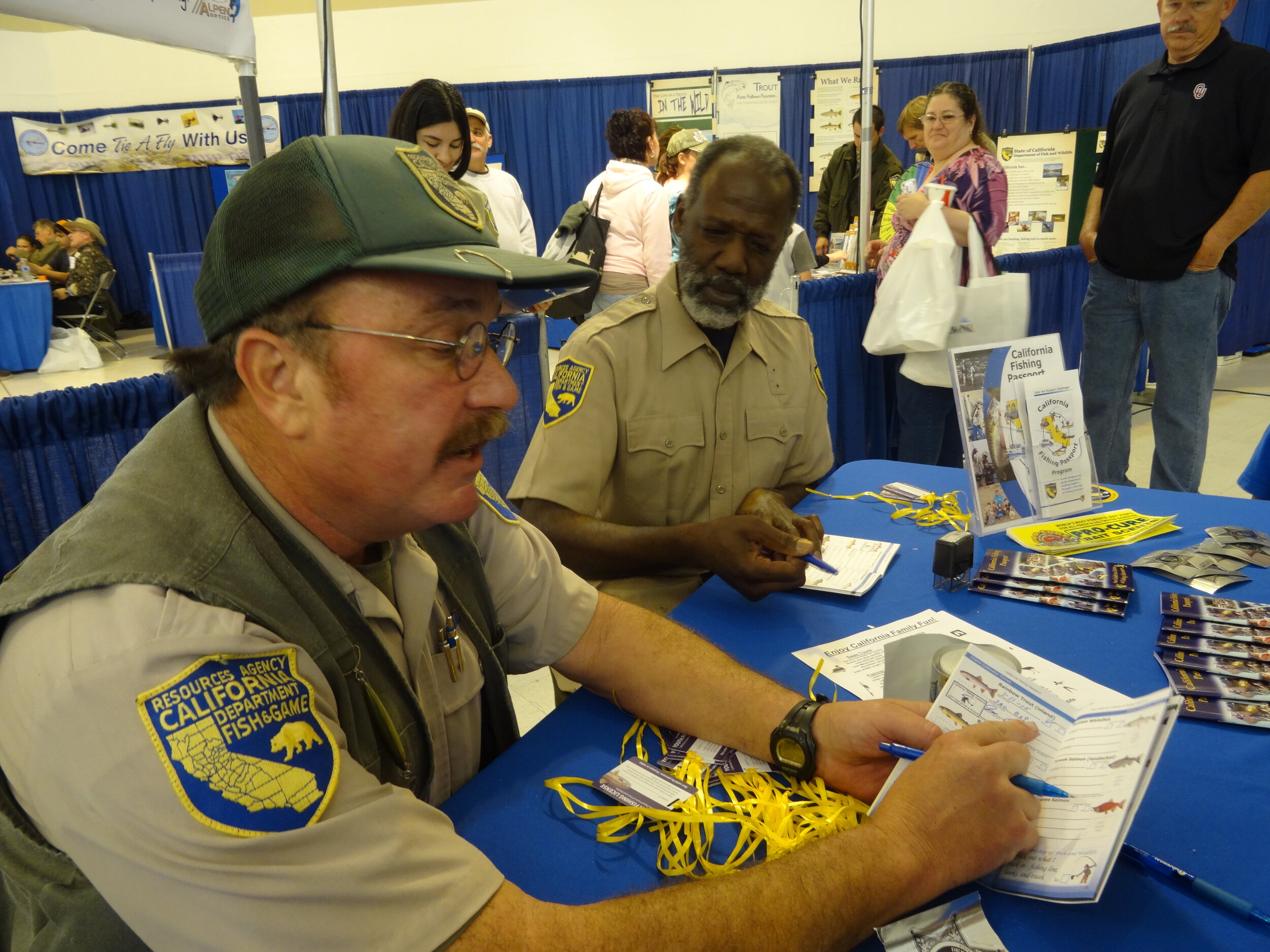

© California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Agencies must strengthen working relationships with hunting, fishing, and trapping individuals and organizations while also working to create new relationships based on shared values.